The Mistake Of The Children's Liberation Movement

Is empowering children more important that giving them rights?

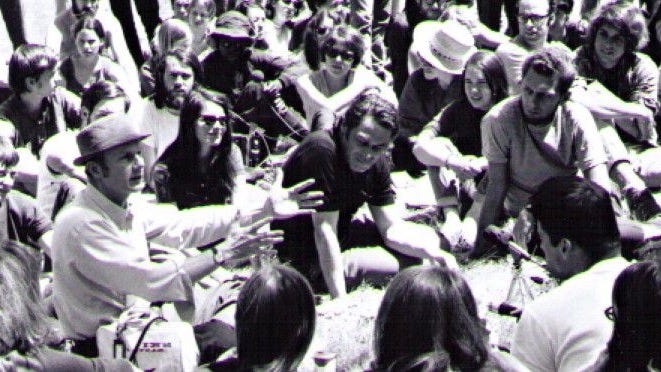

The children’s liberation movement was a social movement for children’s rights that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s. This movement was my first introduction to children’s issues as a teenager when I read books like Escape from Childhood by John Holt and Birthrights by Richard Evan Farson. While I appreciate many of the ideas and intentions of this movement, the research and thinking I did while writing Children’s Justice has led me to see a fatal flaw in their thinking.

First, I’ll say what I like about this movement: Children’s liberation has a genuine concern for the feelings and well-being of children. Many of their issues such as ending compulsory schooling and corporal punishment of children also matter to me. We have more in common than differences. However, there are a few key issues, such as their attitude toward children and sexuality, that make it impossible for me to endorse the movement. The difference in our thinking reveals important truths about children’s issues.

The children’s liberation movement supports giving full rights to children. When they say rights, they mean all rights. Children’s liberation authors have proposed giving children the right to choose their own home, determine their own education, be free from physical punishment, travel on their own, live on their own, have their own money, have sex, use drugs, vote, and drive. In other words, children’s liberation is a movement that aims to give children full adult legal rights.

Most people intuitively understand that giving a child the right to drive, have sex, or use drugs is a bad idea. However, those who support human rights might not be able to articulate why. If rights are good, why would a child with more “rights” be more likely to be harmed than a child whose parents hold their rights?

Suppose we gave a child all the rights children’s liberation authors propose. What would immediately follow is exploitation. While the child might have the “right” to control their own life, they would not have the ability to secure their interests. They would not be able to evaluate others’ intentions or think through the long-term consequences of their actions and be exploited by adults because they don’t know any better. While a child in this situation might have rights, they would not have power.

Giving children the right to study what they want or be free from corporal punishment increases their power. It empowers them. Giving children the right to drive or use drugs opens them to harm and decreases their power. It disempowers them. If you go through the list of “rights” children’s liberation authors propose, those that people intuitively feel are reasonable are those that empower children and those that seem unreasonable are those that disempower them. Power is the actual metric by which to evaluate children’s issues, not rights.1

Children biologically do not have as much power as adults. There are significant aspects of the world they cannot understand or function in without help. Since children cannot meet their needs on their own, the most empowering experience for children is to have adults who use their power to meet the child’s needs — in other words, parents.2 Giving children “rights" without the ability to meet their needs is disempowering.

The push for children’s rights is a reaction to adult treatment of children that centers the desires of adults rather than the needs of children. If adult’s make decisions for children intended to conform children to adult desires rather than meet needs the child cannot meet on their own, that disempowers children. However, if the goal is to meet children’s needs then giving children the “right” to live on their own but not the support to live still doesn’t meet children’s needs. Adults using their greater power for the benefit of children does meet their needs.

The application of children’s liberation ideas to sexuality is the most problematic aspect of the movement. Children do not need adult sexuality, so giving them the “right” to participate in that can only result in abuse and exploitation. There have been some monstrous ideas promoted under the guise of “liberating” children around sexuality. This aspect of the movement alone is enough for me to disavow it.

Part of the challenge of the children’s liberation movement is the word child itself. The legal definition of the word child includes anyone under the age of eighteen. While there might not be a legal distinction between teens and toddlers, there is a significant power difference between a seventeen-year-old and a four-year-old. This power difference is the reason some societies give some teens rights that children’s liberation activists are fighting for (like the right to drive) while denying them to infants. Since both teens and infants lack rights from a legal perspective, children’s liberation often treats them the same, despite the obvious differences visible when viewed through the lens of power.

I first encountered children’s liberation writing as a teenager. At sixteen and seventeen, the rights they advocated for would have been empowering for me. I also knew that as a child many of the decisions adults had made for me were not empowering. I did not have an image of what adult advocates would look like, so no advocate seemed better than a bad one. At the same time, I was unaware of the worse possibilities that might have occurred had I been entirely on my own as a child. While children’s liberation would have solved some problems, it would have created others. What would have been better would have been adults who supported me in achieving what I wanted rather than trying to mold me into what they wanted.

Rather than a children’s liberation movement, what children need is a children’s power movement. It might be challenging to imagine what a movement intended to empower children would look like, since “power” movements for other identity groups often frame power as a zero-sum game, where if one group has more power another group must have less of it. Power can be a positive-sum game, where if one group is empowered everyone benefits. Empowering children benefits everyone.

The article uses Amazon affiliate links.

Sidenote: This distinction between rights and power has implications for other movements. For example, part of the reason that women’s happiness has decreased as their rights have increased is that forms of power women previously had access to have disappeared. Women have the “right” to work but often lack the power to choose whether or not they work. Likewise, forms of social power women had access to have completely disappeared. Since these powers were often hidden and unrecognized, women lack the hermeneutical justice to talk about their disappearance. Instead, they are told about all the new rights they have, which acts as a sort of gaslighting for the powers they have lost. Like children, women would be better served by a women’s power movement than a women’s liberation movement.

Ideally, everyone would behave in the interests of children, but let’s start with parents. While others might advocate for children, parents are the only adults with responsibility and accountability for a child’s wellbeing.

I’m pretty sure Holt still believed that “child” was a useful distinction for a person with a protected status. He just didn’t think it should be based on age. If people want to stay children after 18, protected from having to work but also having no right to vote, perhaps they should be able to. And if a young person wants to accept adult responsibilities and rights earlier than others would, what right do others have to prevent them? I’m confident there’s a way we can protect the innocent and empower the bold and responsible regardless of age.

Apparently this puts me in disagreement with awful people on, I imagine, the internet, but I don't think "other people not being punished for having sex with you" even approaches being a right, especially with how few under-18 demographics actually want this at all, whereas it's no projection to say that many minors of different ages want to escape difficult living situations or to make choices like reading a valueless book at 1 AM, for instance. Laws against having sex with children punish adults, not children. Drugs are typically illegal. Driving is also more a privilege than a right. However, I want to see more long-distance bike/walking trails. These already exist, and to grow up near one is to grow up with the hope and leverage of awareness of ineradicable recourse. Social media is killer on young people's mental health, but who can blame them for using it, when they're not offered anything that matters or any source of agency other than the very equal-opportunity act of yelling at people on Twitter? Long-distance trails reward physical competence with agency. They create a relationship between the self and the world that is mediated by no one else. On the other hand, social media offers very real power, if you think of the right moves. In the real world today, teenagers do run away, and get kicked out, and take refuge in queer communes, which are easy to find online, and some of them do get exploited. To have "real" power to avoid exploitation would be to have better options. To have better options seems like a major anti-capitalist-exploitation project. Child labor laws are to clean up a mess that capitalism made, and they also add endless problems for young people's agency or power in a capitalism-dominated society, for which solutions are antithetical to the structure of capitalism. Unfortunately, I'm not the most optimistic that we can have a leftist utopia anytime soon and without damage to something else. Something short-term in the vein of women's shelters or youth hostels would be a good step. The other route that seems viable is that the same institutions that supposedly prevent abuse from running rampant in the home (homes being tiny dictatorships and all) could be directed towards alternatives chosen by young people. I think forcibly returning a kid to an unwanted home or institution is an injustice that, at best, is the result of a rough world. We can't necessarily cure cancer, but we can say that it's unfair and undesirable.